- Y.SH

- information

- 10691 views

- 0 comments

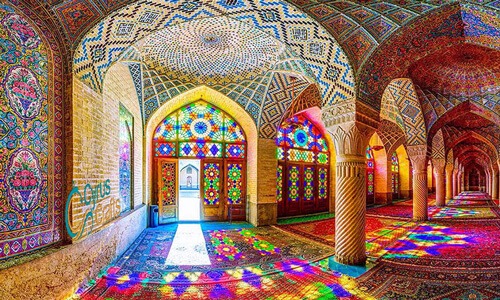

During the 13th and 14th centuries, potters in the Iranian city of Kashan produced one of the world's most sophisticated forms of tilework. The luster was ordered for the day's finest palaces, mosques, and tombs, distinguished by a metallic sheen that shined like the sun.

The Definition of Tilework

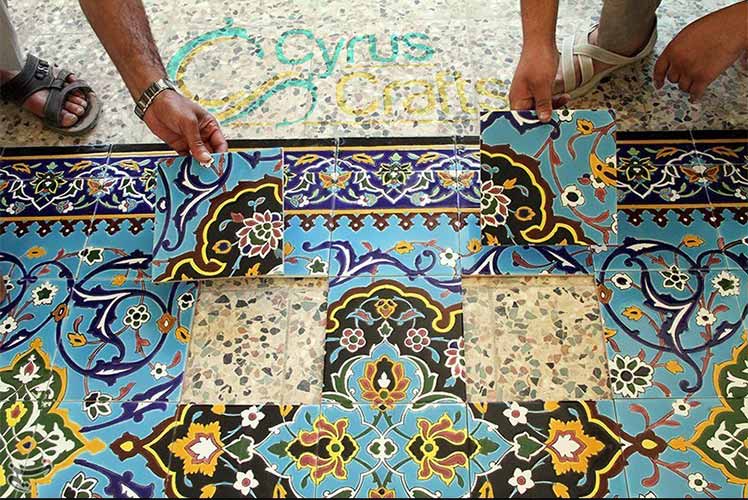

Tiles were used to decorate monuments from early ages in Iran. Mosaic patterns were the first step in the evolution of tile decoration. Imaginative and creative artisans put together mosaic patterns using bits of colored stone and brick and created patterns of triangles, semi-circles and circles in harmony with the structures they were placed on. These patterns later evolved into the design of natural subjects, such as plants, trees, animals, and human beings. The earliest examples of mosaic patterns have come from the temple's columns at Ubaid in Mesopotamia and are attributed to the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE.

Here, colored pieces of stone have been juxtaposed with shell and ivory to create geometric patterns. These early mosaic patterns are the roots of later tile art. The first glazed bricks, further advancement in tile art, have also been discovered in such sites as the palaces of Ashur and Babylon in the same area. A famous example of early tile art on wares is the mosaic rhyton found in the excavations at Marlik. This vessel has two shells. The outer shell is covered with colored pieces of stone. This object is known as "Thousand Flowers." One of the earliest examples of Iranian tile work on architecture is glazed pieces of unbaked brick, excavated at Susa and Chogha Zanbil and attributed to the end of the second millennium BCE.

Cyrus Crafts; Luxury & Unique Products

Earlier Persian Tiles

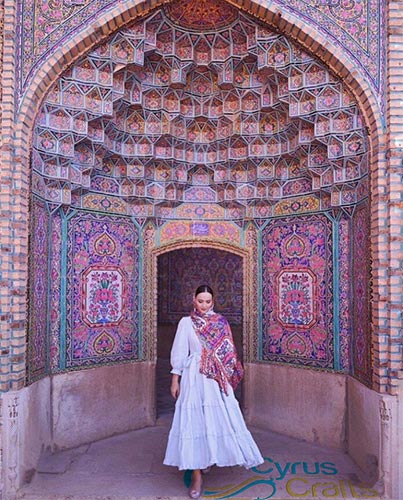

Tilework is one of Persian architecture's most prevalent and vital forms of decoration. Throughout history, it has bestowed a unique and charming aesthetic characteristic upon the region's buildings. The oldest examples of this method in Persia can be dated back to the 13th century BCE in Khuzistan, where glazed bricks adorn the walls of Chogha Zanbīl, an ancient Elamite temple complex near Susa. The same technique was also used during the Achaemenid Empire in the palaces of Susa and Persepolis, a portion of which can be seen in two friezes known as the Lions and Archer's frieze.

Persian tile work reached its full potential during the Islamic period, and artists began exploring various methods and designs to elevate this art to its apogee. Maintaining the ancient practices of the pre-Islamic era, the artists modified both the shapes and thickness of the tiles, as well as the motifs used to decorate them. The tiles became relatively thinner since they were now used to cover surfaces built with burnt rather than sun-dried bricks, and as for the shapes, it can be seen that the more rectangular forms are now accompanied by more complex conditions such as four and eight-point stars.

One can observe a close connection between Persian pottery and tile work techniques which, depending on the differing demands of the patrons, would also change over time. One of the primary and best-known types of Persian tiles is Haft Rang.

Types of Iranian Tile Work

The designs created with these tiles can be seen clearly on the walls of mosques and buildings left from the Qajar period or earlier. Various types of Persian tile work were used in the walls and ceilings of many buildings during this time, giving a beautiful appearance to their facades. The following sections will discuss the different types of designs.

Persian Mosaic Tile

Persian mosaic tiles consist of small and large pieces with different patterns, colors, and textures. They form one complete image when arranged according to the design on a surface (such as a wall or floor). (Of course, there are some differences) In the Persian mosaic tile, white, dark blue, turquoise, green, and orange colors are usually used. Now people in many countries, especially the United States and Canada, have become interested in tiling. Now people in many countries, especially the United States and Canada, have become interested in tiling. In addition to historical buildings and mosques, mosaic tiles are used in Iran for decorating the walls of houses, photo frames, and mirrors.

Moaqli Persian tiles art

Moaqli tiles are made of very small dimensions, and their work involves placing these small tiles side by side. At times they are combined with bricks to prevent expansion and contraction due to cold or heat—this prevents the glaze from cracking.

Moaqli tiling uses various straight lines in the vertical and horizontal axes and diagonal lines with a 45-degree angle. If Kufi designs are used on walls or floors, Moaqli tiles should be chosen because they work best when creating such patterns. This style of tiling can be seen in the buildings and mosques of Mashhad, Iran, Neishabur's tomb for Mohammad Mahrooq (or "The Lady Who Cried"), Isfahan's Jame Mosque—as well as its head design.

Persian Enamel Tile

This Persian tile is usually decorated with Eslimi, Khatai, and vegetable designs. It is mostly blue but can also be found in green or white varieties. Its use has traditionally been limited to the exterior of buildings; however, it has recently become popular for interior decoration as well.

Decorative enamel tiling, which can be found in the old buildings of Iran and dazzles tourists' eyes, is also one of Iran's traditional decorative arts. Enamel tiles, just Like enamel dishes, in traditional architecture, were often blue, making them suitable for minarets or outside buildings. Enamel tiles tend to be decorated with patterns of flowers and leaves; birds; intertwined curved lines; small dots that form a diagonal row across the tile surface—or large ones positioned close together along it. Traditional enamel tile colors include: light blue, dark blue, red, yellow, and brown; green is also a common color.

Seven-Color Persian Tile Works

The Haft Rang tile was cheaper and took less time to create. One reason for such efficiency was that instead of the small pieces of tiles in the technique of mosaic tile, the tiles were now cut into different size squares, which together would form a much larger part and cover a much vaster surface. Another reason was that while in the mosaic tile technique, each color was fired separately, the Haft Rang tiles allowed the artist to fire all the colors simultaneously, separated from their adjacent colors with a manganese outline to avoid them from mixing. There is a belief that one of the reasons for the development of Haft Rang tiles and the necessity for efficiency in time and expenses was the decoration of the Abbasi Great Mosque in Isfahan, which required covering a vast area with tiles in a brief period of time, something that wasn't possible with mosaic faience, prompting the artists to employ this approach in future mosque construction.

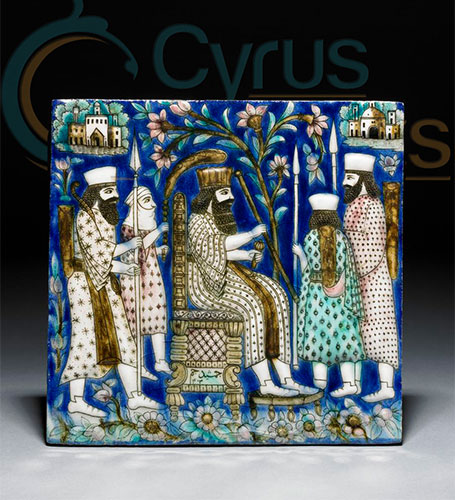

In the technique of Seven-color, the possibility of firing all the colors at the same time, the ability to draw directly on the tile itself, as well as the tile's larger surface allowed the artists to explore various patterns and designs with higher levels of detail and accuracy such as the illustration of human figures. It was impossible to execute this degree of accuracy with the technique of mosaic faience. Depending on the use of the building, be it secular or religious, the patterns ranged from foliage and animal patterns and figures to beautiful pieces of calligraphy. While foliage designs and calligraphies could have been used in the decorations of both secular and religious buildings, the animal and human figures were mostly kept to decorate secular buildings.

Haft Rang does not necessarily mean all seven colors were used in every tile or the entire composition, although that might have been the case in some instances. In some examples of Haft Rang tiles, the artist has even chosen to use only two colors to execute the design, such as the beautiful pieces of white calligraphy, which are performed on a cobalt blue background, representing beauty in simplicity. The primary colors used in this technique are black, white, turquoise like turquoise jewelry, yellow, rose pink, and cobalt blue.

Tile is still beautiful and valuable. But today, the use of traditional tile in Iran is limited to religious buildings or buildings that insist on conventional standards. There is little sign of creativity in most buildings, which are imitations of the lower structures of the past. The spread of Western culture in the native culture and the resulting historical discontinuity have meant that tile, as a traditional element, has no proper connection or function with modern architecture and is considered more of a museum object.

Comments (0)